Image of Nothing, Image from Nothing:

Anneli Sanaye Henriksson

on grids, constraints, and patterns

interview by Tony Wei Ling

Tony Wei Ling: Thanks for agreeing to talk—and for showing me all this new work.

Anneli Henriksson: I've been working on building up some new work recently, partly because I’m applying to grad school. But also because the last time I spoke about the California comic in public, I had this feeling afterward like, “This isn’t me anymore.”

TWL: There’s also a pressure for artists to always be making new work, which can be helpful in some ways but imposes certain expectations about pace.

Anneli Henriksson: That's something I've been thinking about a lot. Between my chronic fatigue and what I’ve started to describe as my delayed processing, I can't get annoyed with myself about how long something takes me, and I have to stop myself from comparing my current experience to my past ones.

Time has become an important element in my work, or which makes sense, because I've always been drawn to narrative art, and so time has always been a factor. I have a whole monologue about Christian Marclay’s The Clock that I've subjected people to a few times.

TWL: Subject me to it.

Anneli Henriksson: The Clock is this shining example of great art that I’ve never actually seen in person. I’ve only managed to see some pirated clips on the internet. Marclay took clips from movies and television, anytime a clock was on screen, and he made it into a 24-hour clock, which is always shown in “real time.” It’s surprisingly emotional to watch. He hired people off of Craigslist to watch movies and to find specific timestamps, and it creates this uncanny history of Western film. The Clock is usually only shown in fine art institutions, so access is part of the experience of the film. Like if it's only shown these institutional conditions, has anyone watched the 1am parts?

TWL: I’m also curious if certain times tended to be sourced from different film genres.

Anneli Henriksson: Right, you start to pull up these different patterns. I first encountered The Clock through its book component, which uses the format of the book beautifully—you can stop time, go backwards in time, even change the narrative by how you page through it. I love publications because of that intimacy between object and reader. And as a chronically ill person, I love that the book can travel for me.

Marclay’s earlier work was all about physical media; he had this huge old studio filled with stuff. Then his partner got a job in London, and he got rid of everything to go with her. Figuring out how to make things work under his new constraints led to The Clock. It’s corny, but I love that suddenly, under radically different constraints, he made his most successful piece.

Before I got sick with MS, I was also kind of a nut about materiality. I mostly did fiber art: very labor-intensive, tiny-thread embroidery and weaving. Once, I made denim from scratch, dyed and wove it, drafted a jacket pattern, and tried to make it.

TWL: Going for the perfect denim jacket?

Anneli Henriksson: I just wanted to have complete control. But later, when I got sick, I started to lose my eyesight; that’s what triggered going to the hospital. Just looking at things hurt. I had optic neuritis, or inflammation of the optic nerve, which is common with MS.

I also developed a tremor. It was a pretty minor tremor, but part of my skill set had been a dead steady hand. I was in the middle of an intense embroidery project then, and I was so fatigued that my reaction was just, “I’m done. I don't want to fucking deal with any of this shit.” That's why I started drawing. To my mind, it was the simplest, most constrained material: paper and a pen, ink and a paintbrush. It felt like what I could handle.

TWL: What was it like, going back to drawing?

Anneli Henriksson: Actually, I had never really done much drawing. When I started college in 2009, representational drawing still felt very uncool, though it was on the come-up—I remember Vitamin D, a survey of contemporary drawing, as this bookmark of drawing’s acceptance in the fine art world.

I was twenty-five then, really into the DIY scene, living at a space where we could have shows and art music shows and art shows. I was dating a cartoonist, and the roommates were also cartoonists, so I was around people whose vibe was “drawing eight hours a day.” That exposure and proximity to people interested in experimental literature and comics was kind of serendipitous; it’s an influence I'm very grateful for.

There’s a certain magic to drawing, in that you can make an image of nothing—or an image from nothing, rather.

TWL: Oh, I like that first phrase, though, “an image of nothing.”

Anneli Henriksson: Of nothing and everything, right?

TWL: The Sunday strip from your Atmospheric River series feels like an image of nothing. I love that one.

Anneli Henriksson: I’ve gotten good at the graphic, symbolic kind of imagery that’s not exactly what you're seeing, but grabs a feeling. For me, comics have been a good way of expressing emotion. I love the constraints of narrative structure and the book format itself, which you can play with, but you can’t escape.

TWL: This reminds of the page you did in California with a border of panels around the circumference of the page, and a little guy walking on that looped path.

Anneli Henriksson: Yeah, I'm happy with a lot of the structural choices I made in that zine. You know Joanna Drucker? She’s written about artist books, and she talks about the history of publishing going from the scroll to the codex, and now back to the scroll. There's so much more to think about with that: the infinite scroll of online, trying to put a book format on digital things, TikTok changing our brains.

I've never really published stuff online. I wonder if I’ll ever need to do that.

TWL: It does feel notable that your online presence is both limited and specific. You've described being into materiality and the book, but is there anything else that makes online publishing unappealing to you?

Anneli Henriksson: It probably directly ties into my childhood experiences of escapism and comfort via books and magazines. In a perfect world, I would love to be able to screen print all my comics into little handmade books, Lilli Carré-style. When I was an intern at MCA, they had a very complete collection of Carré’s handmade books. Since I wasn’t getting paid, my boss let me flip through the new acquisitions of artist books that I was cataloguing—really look at them. It was great because those objects are so rarefied and hard to get, and I think I just really like objects. I have ADHD, so with digital stuff, I can be very much like, “I can’t see it. It doesn’t exist.”

TWL: Now I’m thinking about how different it would be to see Marclay’s Clock on a browser. Museum installations make you so aware of being in a rarefied public space where people are literally being paid to watch you—whereas a book, even a rare or expensive book, can theoretically be anywhere.

Anneli Henriksson: You can be in your bed. That's something I appreciate more now that I'm sick and more tied to home, especially in California. The big subtext of my California comic is that I hate the weather here. I have a very extreme heat sensitivity; it triggers this funny reaction—not an actual MS relapse, but the feeling of one. It feels like shit. That’s why it’s important for people to be able to experience art at home.

TWL: Yes, though the screen is sort of an unholy combination of being at home and being watched in public.

Anneli Henriksson: Yeah. I could see myself posting things onto my own website—I've thought about that—but I don’t think I'd want to put my work on something like Webtoons.

TWL: Those are pretty different. contexts. I do wonder what kind of expectations Webtoons would set for people reading your work.

Anneli Henriksson: Expectations are interesting. When I showed my dad my comics—he's Swedish—the first thing he said was, “Aren't comics supposed to be funny?”

TWL: I actually do think your comics are funny!

Anneli Henriksson: Coming from him, it wasn't malicious or anything—but that was something I thought about. All the comics I sent you were made using Ivan Brunetti’s Cartooning: Philosophy and Practice, which is basically his course. Working from that book was the first time I really thought about being funny; usually, I feel like trying to be funny is unfunny. But that book also starts deconstructing the four-panel narrative: setup, conflict, action, resolution.

TWL: How was it making these strips in that four-panel narrative structure?

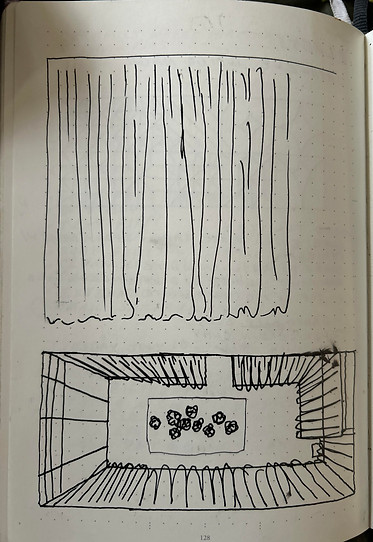

Anneli Henriksson: Actually, give me one second, I’ll grab the sketchbook I did all the Brunetti assignments and notes in.

TWL: Oh—you arranged the four panels into squares instead of strips!

Anneli Henriksson: I did that just to fit the whole strip onto one page.

TWL: But do you have a preference between those two formats—the row versus the square?

Anneli Henriksson: I like the square better because you can go up, down, around…

TWL: Huh, when I was first writing about all the snails and spiders and woven shapes in your work, I hadn’t thought about the fact that you have a background in textile art.

Anneli Henriksson: Actually, the first comic I ever made used an antique weaving draft—a Victorian crazy quilt—for the panels, as a structure to insert my images and my text into. A classmate asked me to contribute a couple pages to a mutant-themed zine he was making. The originals are up at this art residency in Providence.

Oh, but I grabbed this sketchbook because you asked about narrative structure! I started looking into different Japanese narrative structures. There’s the three-part structure, jo-ha-kyū, which stands for “beginning, break, rapid”—actions or efforts begin slowly, speed up, and then end swiftly. There’s also the five-part structure of Noh plays, which is cool because it begins “slow and auspicious.”

I’ve also been looking at yonkoma, the traditional manga gag structure. It doesn’t matter to me if anyone knows where the structure comes from, but it’s helpful for me.

TWL: It’s like a set of different constraints that you can select or move between.

Anneli Henriksson: Clearly, I like installing constraints on myself. Constraints and patterns. Back when I was weaving, I remember having to prepare the warp in a specific way for weaving. You have to stand and use your entire body as a warping board, doing this whole-body motion over and over and over again. And you need to keep each thread next to each other, because the length and the tension really matters.

When I was doing that for the denim project, it took me twenty-five hours just to prepare. If I had a problem, I would be thinking about it while I warped, and by the time I finished, I’d also have figured out what I was going to do. It gave me the right meditative space for me to calmly reflect. I wish I had a big loom like that now.

My BFA thesis was one of the first drawings I’d done in a really long time—a weave draft that I made into a large weaving with the digital Jacquard loom. It’s funny that I got back into drawing by drawing weave drafts. For the Jacquard, I also had to learn how to use pixels, because the Jacquard loom uses white and black pixels to represent the lifting or dropping of a heddle. Of course, the whole thing with Jacquard weaving is that it's the proto-computer.

That was my period of becoming obsessed with the thought that everything is a grid. Everything can be broken down into the Jacquard binary of zeros and ones. I was into that for a long time. When I did embroidery, I did counted embroidery, which means you're using every single thread of the substrate and counting them. All controlled by the grid. With comics, I was just zooming even more into the grid.

TWL: It’s interesting then that your drawings often feel quite loose. Not in the sense of having been drawn quickly, but in the way you approach shape. How do you think about moving from weaving—this controlled but whole-body gesture—to drawing in a book?

Anneli Henriksson: One thing about my drawings is that they’re skilled drawings, but they’re also not good drawings, really. Sometimes they don't seem dynamic enough, compared to other comics.

TWL: They have a lot of stillness to them, but I like that. It's funny to hear you say that they’re skilled but not good drawings. The second panel of the Friday strip actually feels so reminiscent of that classic negative space drawing exercise. Learning that skill always means drawing a chair, for some reason.

Anneli Henriksson: At a certain point, drawing is an automatic thing: I’ll draw a page, throw it out, draw another, and draw it again. Roman Muradov, who mentored me on the California comic, has a similar process of making a lot of drawings quickly and taking the best one. I don’t work quickly at all, but there's something about quickness and repetition. For me, even if the actual physical drawing is quick, the processing is slow. Maybe it's that tension that makes the results a little unique.

TWL: I'm interested in where the slowness of processing happens, if the drawings themselves are quick. Do you feel like that processing happens primarily before the drawings are made? After?

Anneli Henriksson: Oh, every move is kind of slow or deliberate. I just had to figure out a way to keep making art. Brunetti says something similar in the intro to his book—something like, “if I lost my hand, I would use my bloody stump to scrawl cartoons on the cement sidewalk!”

TWL: Very Shakespearean.

Anneli Henriksson: But besides all that, I believe that just looking at art is important. Which feels like a stupid thing to say.

TWL: I don’t think it is, especially since we were just talking about your eyesight and looking becoming painful. Looking is meaningful because it’s a loaded thing.

Anneli Henriksson: Yeah, that’s true. I've spent a lot of time looking at art and looking at images; I’m definitely a compulsive image-scroller online, and I love finding obscure books, too. Curating and collecting visual references really helps inform my work. It’s like a cheat for not being that great at drawing.

Recently, I’ve been looking at a lot of Japanese drawing and cartooning books on eBay. I haven’t bought any, but I’m jealous that they have so many of these insane reference books. It’s also frustrating to know that there’s weird, niche manga out there that I’ll never have access to. I want to make weird books!

I told my friend recently, “I want to read a comic that's weird, with interesting narrative, and I want it to be girly.” I feel like girly is such a stupid word that I love it.

TWL: I'm glad it's made a comeback recently.

Anneli Henriksson: Yeah, I want to be—what's his name? That Chicago comics guy who has a face that looks like a ham. The Building Stories guy.

TWL: Oh my god, Chris Ware? Sorry, I’m laughing at the description “face like a ham.”

Anneli Henriksson: I only said that because he's described himself like that!

TWL: I mean, speaking of obsessive people who are really into grids.

Anneli Henriksson: I want to make girly Chris Ware. I want to be girly Chris Ware.

TWL: Okay yeah, I love that vision. Can you say a bit about what girly means to you in this context?

Anneli Henriksson: I’d just go off my own intuition and interests. I haven't read that many Japanese comics, but I was reading Nana for the first time and I just love the storytelling and the way it looks. I wish the story itself didn’t fucking suck.

TWL: What irked you about it?

Anneli Henriksson: The cliche of it, I guess, but actually the biggest takeaway was, “Damn, I would have eaten this shit up if I had read this when I was fourteen.”

Something I feel is ironic is that my art got better after MS. I was finally ready to imbue my work with some kind of content. Being in Chicago, and in the art world, it's really white. That’s one thing I'm really happy about being in California. I hate California in a lot of ways; that’s the other subtext to that California comic. My mom's parents were in the internment camps. They were born in California, outside Fresno, and their parents were immigrants to California from Japan. So I'm fourth-generation Californian.

TWL: You have the cred to really hate it.

Anneli Henriksson: Those of us that hate California, it's because we remember what it was like before. A lot of people in my family, including my grandfather, went to UC Berkeley; my parents met there, and my mom spent almost a decade at Berkeley to get multiple degrees. So for a long time, I was rejecting Asian American California as an influence. Now I’m realizing that it’s also the experience of my grandparents; it’s had a huge impact on my life, and my family's life. That’s something worth digging through.

It's also nice to be somewhere that I feel a little bit more normal, blend in a little bit with the crowd, where I’m not the only Half-Asian Art Girl. At this point in my life, I'd rather be able to relate to people, especially other biracial Asian people.

TWL: There's definitely a lot of us here.

Anneli Henriksson: It’s funny to say, but maybe I’m fascinated by the UCs [Universities of California] right now because I want an experience that mirrors my relatives’. Some of my earliest memories are being on Berkeley’s campus, and that was actually a good time in my life.

TWL: It sounds like the UCs have been a big part of your family history, as well as a big part of Asian American history.

Anneli Henriksson: Yeah, it's corny, but I've told my friends: art's hard! A career in art is hard. I'm still in it because representation still matters. How I felt about it growing up is a total cliche—but I’ve been trying to think about cliches as patterns, because I like patterns. So, how I feel is a pattern. Tale as old as time. But I'm the only biracial person in my family. I have some totally Japanese family and some totally Swedish family. When I was younger, I wasn't able to understand how that's what was making me feel so terrible.

Some funny Asian American comics gossip is that my cousin, or second cousin, Rob Sato—he and his wife [Ako Castuera] are both artists in LA. I actually haven't met them in person, haven’t met that side of the family, but we’ve talked on Zoom now. That was my first time talking to a relative who’s also biracial. Rob and Ako are both involved in cartoons and comics, and they’re the coolest people ever. They both came out of CCA [California College of the Arts] on the tail end of Beautiful Losers era.

TWL: What’s the Beautiful Losers era?

Anneli Henriksson: Oh, Beautiful Losers is this documentary of Bay Area artists—Barry McGee and Margaret Kilgallen were the biggest names—and that whole scene. A lot of them are in LA now, connected to the Asian American art scene. They've done a lot with the Giant Robot people.

TWL: Oh yeah, that’s a local landmark. I’m glad you could connect with your cousin—funny that you both make comics!

Anneli Henriksson: We actually ended up having very similar media references and gaps—neither of us had a lot of manga or anime growing up, just Sailor Moon.

Oh, you'll love this story. I had a very close relationship with my Japanese grandmother, and she would take me with her to J-Town sometimes. We’d go to one of the gift stores that had comics, and I was always very interested in it. My mom was always a bit skeptical of manga because of the boobs, the hypersexualized vibe, the guns, which I get.

But one time, my grandmother told me, “You can buy one book.” It was all imported, so it was really expensive, probably like thirty dollars or something—this is the early 90s.

I picked out this one volume of Sailor Moon. And it wasn't the first one. It was one from the middle, and it was black and white, and in Japanese, and it was backwards. I just had that one book, but I was obsessed with it. I would carry it with me as a comfort thing. I was an only child with a divorced mom, a single mom, so I spent a lot of time alone. I would read it, and I would try and make up my own story—to fill in the bubbles, to create a narrative from the image.

I only realized how formative it was for me a couple years ago. It was funny because I didn't really know any of the lore, so it was all from me. I really want to get a copy of that again and redraw it, write my own story in it.

TWL: Visually, I do feel like there’s some connection between your work and hers. Naoko Takeuchi’s line has that spindly quality. Obviously, she liked to draw extremely thin and tall figures, that fashion illustration thing, but there's something really structured and delicate there that reminds me of your drawings.

Anneli Henriksson: Do you know Heather Benjamin's work? She doesn't make comics, but her work strongly references comic imagery, and she was obsessed with Sailor Moon trading cards growing up. She apparently realized that some of her images look just like those cards—the patterns of composition, the subject matter, even the boots! I made that my Sailor Moon connection from reading her talk about making that connection.

TWL: Do you think that Heather Benjamin's work is girly? Because I do feel like Sailor Moon is at the center of whatever girliness is.

Anneli Henriksson: I think everyone has their own personal definition of girliness, and that’s part of what makes it great. I love that everything can be girly if you want it to be, or if you just say it is. The collective I lived at in Providence helped me put together some ideas about femininity and decoration as feminist. Those women were working in the heyday of the early 2000s, when gender was more binary—the masculine white cube versus the feminine ruffle, right?

I love the putting on of the ruffle on a fuck you to the patriarchy. I read that Adolf Loos essay, “Ornament and Crime.” That space in Providence really embraced ornamentation—and ornamentation as crime. It shifted my ideas about how performing femininity can be a form of dissent, and in kind of a funny way, too.

TWL: Ruffles are extremely funny when they’re taken as morally offensive or unserious.

Anneli Henriksson: The gendered ruffle! Something I’ve been thinking about with the girly comic stuff is wanting to find the right kind of tension in my art. Personally, one of my funny tensions is between loving populist art and being kind of a snob.

TWL: That tension seems to come out of DIY art scenes almost naturally. It’s like the principle of “anyone should be able to make this, anyone should be able to have access to these tools” comes with a little impatience. “Turn off Netflix for a second and learn something!”

Oh, speaking of ornament—you’re working on an installation with ceramic persimmons and batik curtains right now. Can you tell me a bit about that project?

Anneli Henriksson: My grandmother really loved persimmons. She was a very organized and disciplined lady—stereotypically Japanese in some ways—but her indulgence was persimmons. As in, she would eat so many when they were in season that her skin would turn orange on the palms of her hands. From the inside, from too much carotene.

My grandmother grew her own persimmons and always submitted them in the San Jose County Fair, and she always won every year. Which is funny, because both of my grandparents were both from very destitute Central Valley farming families. So that was always notable to me, and then of course it’s also an icon in Asian art.

I’m going to make thirty-three persimmons—I wanted an arbitrary, personal number that forms some sort of mass, and that’s my age. I’m making a plinth to put them on, using a flash paint to make the surface real flat, smooth, untouched. It’ll look like the yellow American Spirit cigarette box, which was my brand back when I was a smoker. I was remembering a Marlboro coffee table I saw in some 1970s magazine.

This installation is working from a series I wish I had been able to continue back in school. I’d made a zine about drawing grids, and I wove two images from it. I wanted to have all of the weavings displayed so that you could walk through it—walk through the zine. And then I wanted to photograph the weavings and print a zine out of that.

TWL: A recursive zine… room.

Anneli Henriksson: So that's part of the idea with the batik curtains—to have drawings, the zine, the comic, that you can walk through. To be surrounded by a comic. We’ll see what can actually happen. I’ve been practicing my batik, which involves using a funny little tool with hot wax and drawing on fabric. I might make some digital collages, make those into line art, project the line art onto the substrate, then pencil that in and use the wax. Fabric is a lot easier to deal with than paper.

TWL: In what way?

Anneli Henriksson: Keeping it clean and just handling it in general. You can't dent a piece of fabric, and it’s easier to ship and store.

TWL: Can I ask about the title? “Double Happiness.”

Anneli Henriksson: That's part of my corny interest in Asian American culture. I don't know if it was your work or something else I've been reading, but recently I’ve been thinking about the identity of Asian American. I definitely identify more as an Asian American than a Japanese American.

TWL: It can be more capacious of an identity in some ways. Though certainly not in all ways!

Anneli Henriksson: By the way, there's one art historical reference that you didn't pick up in the thing you wrote about California.

TWL: Oh! Was it the figure lying prone on the bed?

Anneli Henriksson: Yes! That was a reference to Alma Mahler. Alma was this ultra baddie muse, had all these relationships with geniuses. She also was an artist in her own right, but she was apparently a super sexy, charismatic lady, because this other artist was obsessed with her. Total nut. So he commissioned this very famous doll maker to make an expensive, life-size doll of her. For some reason, maybe because the doll-maker thought he was a creep, the doll that was delivered to him had swan skin; it was covered in feathers. He would put her in the carriage, take her to parties—he did the real doll thing, basically.

I felt really proud of having that art historical reference right next to the Animorphs one. I've read about the guy who did the covers, and it was quite a labor intensive process. He was hiring models, having costumes made. A combination of physical and digital effects is this sweet spot of weirdness, and the Animorphs covers tap into that. They're so iconic for our generation.

TWL: I hadn’t considered that they might be labor intensive to make, but that’s kind of wonderful to know.

Anneli Henriksson: I have a fascination with commercial art production, just from being a kid and wondering, “How the fuck do you make this?” And now I’m always wondering, “How do you make money? What are you actually doing every day?” I suppose I’m frustrated that there are commercial art jobs I’d love to do but can’t because of the hours, and how much you have to be able to do, working 16-hour days.

TWL: Increasingly, it seems like no one can do it… Even the people who are able-bodied and skilled and supported enough to do that work, they get less able-bodied from having to work like that.

Anneli Henriksson: Right, Ai Yazawa, the lady who did Nana, left it unfinished because she had a debilitating illness. I enjoyed being a studio assistant, but sometimes I see these huge, crazy installations and think, “how does this happen?” Where does the funding come from? How many people work for you?”

TWL: And who gets named as artist, versus fabricator, versus assistant. Now I’m thinking back to Craigslist and Marclay’s Clock piece.

Anneli Henriksson: I definitely have ding-dong Fine Art aspirations, but my impulsive self is sometimes like, “Man, I would love to design a Kleenex box.” It’s the same reason I love making posters and record covers—art that inserts itself into your life.

That's also definitely part of fibers history, which I’ve sometimes felt some tension about—being female, and identifying and working with textiles. Not that we’re still in Bauhaus times, when women were only allowed to do textiles, but part of me resisted going into fiber art, even though it’s the easiest material for me to get excited about. Am I going to reject that because I don’t like that it’s a prescribed gendered thing? What’s wrong with me? No one cares.

TWL: But people do care. Or that seems to be what you’re responding to. I can see how that might feel hard to escape.

Anneli Henriksson: I do appreciate that labor and Marxism was a big part of the discourse in that program, as well as art historical things like “Victorian women invented collage!” I’m glad I got that perspective. That was also when I first proposed and worked on the concept for the curtain-drawing installation. I remember my teacher in crit saying, “You keep on talking about making these rooms and these curtains. You need to just do it. Why haven't you done it?”

TWL: It sounds like this ambitious concept has stayed with you—which can make it feel both impossible and inevitable at the same time. I’m glad you’re making it now; I think it'll turn out great.

Anneli Henriksson: I mean, I hope it's gonna lead me somewhere. I have a whole crazy plan of redecorating my living space with them after. The best thing for art is to be put to use.

Anneli Sanaye Henriksson was born in 1991 in Palo Alto, California. In 2014 she received her BFA from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. Henriksson has illustrated for a diverse range of clients, including Celine Paris and the Chicago Reader. Her art books and comics have been exhibited nationally at the Los Angeles Art Book Fair, the New York Art Book Fair, the Chicago Art Book Fair, Comics Art Brooklyn, San Francisco Zine Fest and the Chicago Zine Fest. She is a former member of the Dirt Palace feminist artist collective in Providence, Rhode Island. Upcoming shows include “Double Happiness,” a solo show at Minnow Arts, Santa Cruz, California. Henriksson currently lives and works in Santa Cruz, California.

Tony Wei Ling is a comics researcher at UCLA and an editor at Nat.Brut.