I saw an obituary of myself on a lazy Tuesday afternoon. I saw an obituary of myself on a lazy Tuesday afternoon. Before I had repeated that a third time, I saw an obituary of myself and I caught a bubble in my throat and swallowed it. I’d just eaten lunch, had just drunk a soda, and the burb came out sweet and fruity.

This must be a mistake. I was alive, flesh and blood, just eaten and warm with my gabardine slippers, coffee, newspaper. Tuesdays were work days, but I was taking an extended period off from the company, the Albatross, which specialized in a software that, I was ashamed to say, I had no full idea about. I’d gotten lucky at an interview for a typist position. They needed someone to type documents written in a computer language which I had to translate based on a template of codes into another. My vacation would be over soon, I’d been a loyal three year employee, comfortable and not planning to quit. But this right now, the obituary, with my name, year and place of birth, and a blown-up picture of myself, was troubling:

“Liberty B., who first saw life in 1984 New York, upstate, has unfortunately passed on from debilitative neurasthenia in the state psychiatric hospital, with no surviving kins. It was a quiet death, a battle spanning long months on the shoulders of unflagging, lion-hearted nurses and doctors, to which a lesser person would have succumbed earlier. She has been, as a typist at the Albatross Corporation, a conscientious worker always punctual and diligent, responsible and uncomplaining. Known to love the zoo, documentaries of wildlife and nature, trekking in forests, she will be sorely missed.”

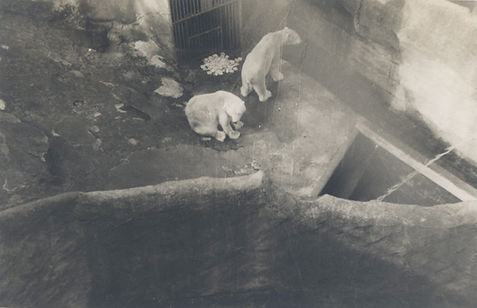

Not a bad way to frame my death, accurate and recognizable to me, certainly so at work apart from the moody spells that struck me randomly. Definitely, my love was the zoo. That I went willingly even in the winter, under snowfall, to find many animals housed in their quarters, construction and fences closing off the sights.

Since I wasn’t yet dead, the point about passing on “from debilitative neurasthenia in the state psychiatric hospital” was debatable. I wouldn’t know if that was a good way to die, only that my ideal deathbed would have been some horizontal surface in my apartment. The bed, my beige couch, the herringbone parquet floor, or the easy lounge chair I was sitting on. A state psychiatric hospital, no offense to the hardworking nurses and doctors, sounded cold and dramatized.

The picture in the obituary was definitely me.

I’d taken the selfie at the zoo with a blurry panda. Right before the shot it was eating shoots, and I hadn’t expected it to move, dragging the bunch of bamboo roots and leaves away. I was a lonely user of Facebook and had posted the picture with the caption, “Gone to see Pandora, Dec. 12.” At that time, many strangers had commented “What great fun,” “Ooo, nice pic,” “Lovely smile,” “Good luck,” and so on. Now, this photograph was used as my obituary. I don’t get it.

Maybe there was nothing to get. Just a prankster doing his job, forging death certs and impersonating a friend or doctor, sending my picture and a fair-written obituary and paying for it to run. The world these days was full of surprises, idle people with attention-seeking problems, wanting to rile each other for…? Just, what did he or she get out of it? Why would anyone bother to make up my death? I don’t get it.

Anyone would say now, something’s wrong with her. Surely she’d done something to get this, no flame without fuel, happiness must have a root, death knows its authors, et. cetera. A stranger willing to pay for a newspaper death that must either be charity or liability. Maybe someone owed her a debt and wanted to repay her but found out (mistakenly) she’d died and no one knew it, poor soul. Maybe she owed something and deserved her death. Maybe it was an advertisement, who knew what for; or the wrong photo of me mixed up with the obituary department in the newspapers that was supposed to be for another article, one like “Loyal Patron of the Zoo with Beloved Pandora.” That still didn’t explain how the text got most of its details right.

I logged on to my FB account. I had fifty likes on Pandora, two loves and three wows, and strangely, four shares. All from people I’d never met, because these things were chains and friends accrued mutually (Oh, he knew Bob), unconsciously, as easy as dreaming, and all of a sudden I had a thousand and six. The reality I walked and talked in wasn’t as generous. Those I could call friends were living miles away and had migrated onto FB along with the new friends, so undifferentiated that I soon thought, what the heck, I love everyone. Obviously I wasn’t an expert, or the obituary wouldn’t have happened. I put the newspaper next to the picture on my screen. It was unmistakably me. The two black smeared bits were Pandora’s eyes.

Suddenly, the platform felt like an electronic city with nice-looking alleyways that’d rerouted to a grave. I was sure I wasn’t the first to encounter this jamais vu; I’d heard about eerie experiences with social media deaths. How was I supposed to find out who’d downloaded my picture, with so many names on the post? I clicked on the commenter who wrote, “Good luck,” with triple love emoticons. The account name was Harold P. and he was an animal lover, living in Ontario.

No conclusions could be drawn. Who was present might not be the one who’d downloaded my picture, what was presented might be the converse of what it was saying, good luck, bad luck, toxic coffee—I knew this much. To go through fifty-nine (or a thousand and six) accounts would be pointless, for even if I found him or her, what could I say? Up for laughs, yes so what, yours truly, the pleasure’s mine? My picture with Pandora had caught the aura of death, I closed the browser and lay back in my easy chair and meditated the evening away, watched some TV, ate and slept.

The next few days, I felt cursed. I wore a hooded jacket and went to the magazine store one block away to get the newspapers. I did that every day (my obituary was still up) till the cashier, a friendly, bearded, checkered-shirted guy in his middle age, said, “Hungry for news, huh?” Normally I’d have chatted about the erratic February cold and latest celebrity news, but I wasn’t in the mood.

“How many copies of these did you sell today?”

“Huh. Can’t remember. Couldn’t be that many, most people don’t want print copies now.”

“I gotta run.”

I’d wanted to see this as a temporary storm, some strange rainy corner at the edge of the world, undetected to anyone who’d known me, Liberty B., at work; or taken my name card at the obscure yearly conference the company sent me (mandatory for typists in my caliber). New codes were emerging that I was required to translate from the stacks. “Better know them,” Rupert, my boss, had said. But online the world was overrun with convenient eyes, in cell phones and homes. I got home, panting from the steep, narrow stair to the third floor, and found my computer.

Yes, there was a digital copy of my obituary exactly like the one in print. What nearly knocked me off my chair were the entries of condolences that followed it. From Helena: My dear colleague! I’m so sorry to hear of your passing! This is so sudden and surprising. I thought you were gone for a vacation. I hope you know how much I’ve enjoyed sitting across you in our cubicles. Listening to your monologues has been a joy. From Bob: I had no idea you were sick. You should have mentioned it. You’re gone so fast. RIP. From Alan: You seemed so healthy, when we sat next to each other at the 2015 Minneapolis conference. I was lucky to have spent time with you. From Jo: I will never forget our high school days. You were a wonderful person. From Aberdeen, someone I didn’t know: May god bless you and your loved ones in these times of sorrow.

Many circles of hell closed in on me. Moved to tears, I reached for the Kleenex box. Just when I thought we were dulled by each other. Getting shushed by Helena and Bob when I muttered too loud. Alan, really, had been quite obnoxious to me at the conference, had at one point pinched my butt. Who’d have known that, reading this now? Jo came from a dysfunctional family. She didn’t have money for lunch (it wasn’t free then), and I shared mine with her. To think she still remembered after twenty years! But did these messages mean they’d gone to the funeral? By now it had already passed, at a funeral home (most likely arranged by the state, the deceased had no kins), with me sick and hiding in bed hoping the mistake had cleared up. I couldn’t gather the courage to attend. I was planning to call the newspaper bureau about the mistake but had not called. Did they actually see me in the coffin, all made up and ready to go?

On FB, there was a post to mourn and tag me from Harold P.: “Very sorry to hear this. Rest easy.” I still had no idea who he was.

Early the next morning, a Wednesday, I had a big breakfast. Two eggs, a sausage and pancake with butter and maple syrup, a bowl of strawberry yogurt. Coffee and orange juice. I brushed my teeth. My hair didn’t need combing, it was short and man-like, but I spread gel on the fringe. In the mirror, I was surprised to see myself haggard, eyes ringed like Pandora’s, lips cracking from the February air, cheeks cratering despite my heavy meals. As though my declared death was eating me inside out. Who was the deceased, the other Liberty B.? The name wasn’t common, but surely there was someone else with the exact same name? Poor soul, to have even her mourning portrait confused with someone else’s, mine.

I had a handful of old make-up in the mirror cabinet. Compact, lipsticks, and a multi-purpose kit. An hour later, I was full of pink life, healthy as a cartoon character, with matte sandy skin and shapely brows, powdered lids and curled eyelashes, apple lips. The spots on my cheeks could cheat death. I swore no one would mistake me as a corpse. At ten I left my apartment, took the orange line to the tail end of the city, near the pier. The trip was pleasant. Sunshine brought the temperature to a warm sixty-eight, enough to ditch my purple coat and sling it on my arm (a nuisance). I was sweating in my best casual wear, denim shirt and jeans, which seemed a mismatch for my colorful face, usually bland as dough. I had glances cast my way, mysterious smiles I didn’t return.

It was a deserted, residential district verging on light industrial. A street running under a railway track. A line of auto and tire centers, lighting and furniture stores, discount depots and dollar shops. My make-up was melting as I searched for the place, coming off the color of mud on a Kleenex sheet, the road was rough even with sporty shoes. By the time I found it, tucked into an inconspicuous lot I’d thought was a carpark, without a sign on the single-story, milk-tiled building, it was lunchtime. It was locked. A sign said, “Be Back Shortly.”

I waited on an asphalt curb where hedges lined the oblong building and protruding, boxy entryway, locked behind black glass. It was twelve o’clock. I tired of loitering and left, crossed the diagonal zebra stripes past a gas station and liquor store, I found an eighties-style diner. The regulars, all elders, were reading newspapers, and one looked longer at me than necessary, moving his head back and forth between me and his paper.

I made my way back at two (left a good tip). Thinking hard about a suitable introduction: “Hi, do you recognize me (cellphone in hand)?” “Hi, did you have a funeral here on February 14, the deceased also named Liberty B.?” “Hi, this picture, that is me, was up at one of your funerals on Valentine’s Day. Did you, by any chance, notice that the corpse wasn’t me?” And so on. I had no clear plan. But I did want to know how many had attended the funeral and whether the funeral home had written the obituary or sent it on to the papers.

At half past two, a minivan pulled into the lot and backed into the building’s garage. Shortly, a man, in a worn, chocolate tweed blazer and knitted maroon vest, emerged and frowned at me for dawdling in his premises. He had a gold pen clipped to his chest pocket. The grave frown dragged down his face.

“What do you want?”

“I wanted to find out about a funeral package.”

“Loved one died?”

“Yeah.”

“Come in,” he said, friendlier. He felt for his keys in his trouser pockets, pulled out a scrunched ball of tissue and wiped his nose before getting the door open. The reception area buzzed with fluorescence, and from behind the counter he handed me a black file. I saw a dim doorway through which an inner hall was visible, chairs lined and divided by a center aisle, a podium beside a microphone below a transom window shiny with the afternoon’s sunlight.

“Here are our packages,” he said. “You can pick and choose the one most suitable for your needs, and we can customize it too. Who was it who’d passed, if I may ask?”

To be fully aware of what I was doing, I wouldn’t be here, caught in a gummy situation. Someone who had downloaded my photographs was lying about my death, was lying to me, not worrying I’d get up from the grave and stand behind him covered with mud and worms and asking him why he’d done this. Well, maybe he knew me, at very least he’d seen my photo, and the more I thought about it I was certain I knew him too. Or was this purely a mistake and the poor deceased girl had no photo whatsoever and had to borrow mine?

Impossible. Cellphones were the equivalent of cameras now. Could they not just take one post-mortem, open her eyes with some photomontage app for the obituary? Plenty of tools these days to fix a hated photograph. The bubble that had been stuck in my throat with a sweet soda scent ever since I discovered the obituary pushed into my mouth. I said, “An aunt.”

“My condolences,” he said. “My name’s Walter. I’m the funeral director. Let me know how I can help.”

I squirmed in the leather armchair, flipping through packages. Some included obituary-writing and insurance claims services. Poor Walter—he was unknowingly getting whirlpooled into this, believing there had been one more death in the world when my aunt was perfectly healthy and uploading pictures of her attending to golf clubs with her boss. The only consolation was that Walter didn’t seem to recognize me, had never seen me in his entire life, which meant: 1) He hadn’t written the obituary 2) He’d forgotten about it entirely 3) The dead girl bore no resemblance to me. 4) My make-up was working too well.

The lie had to go on. Walter was behind the counter, head bent low before a green banker’s lamp. The light cast a circle of dust on the hand with the gold pen at the ledger beside a calculator. When I approached, he peered out of his square glasses, complexion adopting a waxy sheen, eyes old from seeing death in all its nudity, which gave no one a second chance to do what they missed, to repair, or regret. I did what my downloader had done. I said, “I had the greatest aunt. She loved golf. Wouldn’t leave home without her clubs. We had golf balls, plenty of them, around the house. Under the couch, in the laundry basket, bathtubs and beds. Sometimes she rolled them down my back on lazy Tuesdays, after school. I just have all these memories of her and no one to tell them to. She’s my only kin. She died, without apparent cause, last week.”

“Without cause? What did the doctors say?”

“Well, she had severe depression, was hospitalized for a while. But the doctors said this was a case of psychogenic death. That means giving up hope on living.”

“I’m sorry to hear that. I’ve handled suicide funerals. The bereaved in these cases are certainly more distraught. Some believed they were responsible. Package A here would be suitable. It includes everything; we handle it from beginning to end, so all you need to do is grieve.”

“Can you walk me through the process?”

“Sure.” Walter came out of the counter. We went into the inner hall. Lights on, he said, “Here’s where the service takes place. We can seat two hundred. If you want the casket viewed, that’ll be the altar here. The podium is for speeches. I’m assuming your aunt’s body is at the hospital, so I’ll be picking her up and bringing her here. She’ll be washed, embalmed and dressed up in the back room.” He pointed. “I can’t bring you in there, it’s only for staff. Is your aunt religious?”

“No.”

“The funeral would be simpler then. Lots of things show up when a person dies. Some have many visitors, and the funeral goes on longer. Others don’t even have a single visitor. It tells you how someone lived. Then again, I’d seen big funerals trashed up by people who hated the deceased and came applauding. One brought champagne and did a lap dance. Then there are occasions with only two mourners, grieving deeply.”

“What about Liberty B.?” It came out before I knew it.

“Liberty B.?”

“There was a funeral here last week. I saw the obituary and decided to visit.”

“Is that how you found Sacred? I didn’t expect obituaries to be ads.”

“Yeah, I wasn’t sure what to do. Did you write the obituary?” I felt like myself again.

“No. It was an odd case. I remember it because the name, Liberty B., is unusual. There was little to do. I only had to process the death certificate, and the service was only ten minutes long.”

“Did anyone show up?”

“Nope. We get these pretty often. Unclaimed people with no money or family. Usually there’s a body, but in this case there was none. The hospital said they were keeping it. Why do you ask?”

“Poor thing.”

“Some people have ill luck. I see it around here. Luck caused by other people that death eventually noticed. I try to respect it. Dress is how I show it. Ward it off with dignity. Or I’d be gone too. Not talking to you about your aunt. Now, I’m going to give you some forms, and you can fill out the details. We have to file the papers with the registrar soon.”

I looked at my watch. “I have some urgent matters to deal with now. I’ll give you my number and we’ll get in touch again.”

“It’s not a good idea to wait too long. A dead body has to be attended to. You said she died last week, and it’s Wednesday now.”

“Don’t worry. My aunt is in good hands.”

I took the orange line home, sun slanting through the train window, a weight of gold on my face. It was an unexpectedly heavy day, full of sorrow for my namesake Liberty B. She’d somehow come alive at the altar, even though her body was never there. I’d planned to visit the hospital and newspaper bureau, but I lost heart now, knowing why my picture had accompanied the obituary. It was a mistake, but if I’d loaned her some life, a view of myself and blurry Pandora, that might be the best deed I’d done in my life. I had been close to her, bonded by a picture. And as lightly as her life had treaded the world—kinless at death (though my aunt was alive we never meet anymore), unvisited and unmourned (apart from my electronic condolences)—so might be mine.

Before I teared up with self-pity, I’d reached my station. Life moved on in colorful ways, the turns of a skirt or the brown hues of the man playing the erhu; the carefree skips of skateboarders up the stairs and shouts of a man they pushed, past a pregnant woman who fell at the landing, a crippled lady helping her up, picking the scattered oranges. All these made me stop thinking about Liberty. I hurried home, past the magazine store and skipped up the dark stairs sometimes slippery with vomit. I washed my face in the bathroom. All the cakey pink and brown and red swirled into the drain. I made dinner and went to bed.

The next morning I went to work. My vacation wasn’t over but I felt I should cut it short, go in and clear up the misunderstanding. Tell them it was a mistake, I wasn’t dead, all the while I’d been alive at home, and it was someone else with the same name. I went through my routine, no breakfast but a sugarless coffee. No make-up—the horror of the muddy Kleenex the day before had been exhausting. I took my leather tote bag from the stand, untouched since my vacation had begun, and left.

Once more the train sped through tunnels. It emptied at a central station and the stream of people scattered onto the streets. I went west. Two weeks had passed since I was here, and the construction scaffolding had extended itself over a new block, over a cafe and two store spaces up for lease. Danny, the security guard, waved a finger, and I said, “Good to see you.” He was eating a bagel. I had snacks in my pantry corner with “Liberty” taped on the shelf, microwavable lunches and sodas in the fridge. These were missing. The electric kettle was gurgling, but I couldn’t find my name or soup mix or cup. I remembered I was supposed to be dead. They’d probably kept my things, whether they’d visited the funeral to say goodbye or not. My cubicle was emptied too, cleared of my spider lily plant, photograph of Mom, gabardine slippers, Kleenex box, keyboard cleaning goo, water bottle, Moleskine diary, memory foam cushion. I wasn’t sure what to do.

“Helena,” I said, bending over the divider into her cubicle.

She gasped, seeing me hovering over her. “You are dead!” she said. Behind me, Bob stood statue-like, mouth slowly forming the words, “I wrote on your obituary…”

I said, “That was a mistake. Someone used my picture for the obituary, it wasn’t me.” But I might as well have said nothing. They backed away, in a consensus that there could be no mistakes in matters of official death. Soon, the co-workers, typists, data clerks, info gatherers, technicians, analysts, annotators, with whom I’d only had hi-bye-good-morning-and night relations, were looking at me.

I missed Pandora. I wished she’d been properly in the picture, so that no sensible person would download it for a convincing obituary. The office parted to let me pass to the manager’s office. Rupert was in there, munching a muffin that dropped after I knocked and entered. “You—you are—” he said.

“I’m Liberty.”

“And you are—”

“I’m supposed to be dead. But I’m here to explain.” I told him the rest, about the magazine store, the trip to the funeral home, my lie to Walter, who hadn’t called to ask for my aunt’s body…

“And why didn’t you call me the moment you found out?” he said.

“It’s fine now. I’m back!”

“But I’ve hired someone else. She’s coming in tomorrow.”

“So fast? I wasn’t even due back from vacation till Monday.”

“She’s transferring from another department. I thought you were gone for real, for good, so I requested for a new typist with Human Resources. They happened to have a clerk wanting to transfer here, waiting for a space to open up.”

“So I’ll be working there?”

“I don’t know. I mean, I’ve already filed your termination. You’ll have to ask them. I’m sorry.”

I got up. At the door, I asked, “Where’s my stuff?”

“They collected it.”

I didn’t know anyone at Human Resources. They told me they’d cleared out my things, and if I wanted them back I’d have to contact them. They told me that unfortunately, the termination had been processed and was now official, so I’d have to apply for the job again if I wanted to come back. Past employees were quickly hired, Sarah reassured me, I just had to emphasize that on my resume. Make it bold. Right now, they didn’t have any openings for a typist. Clerk positions were full, too. I’d have to wait. She wasn’t sure how long.

“Tell you what. Give me your number. I’ll call when one comes up,” she said.

I left without saying goodbye to anyone. I didn’t want to explain my death again. Rupert had said it was an impossible story, and I agreed wholeheartedly. Had I offended somebody, that he or she wanted me dead? And his questions were answered in the strange new squint he gave me as I recapped what happened. I should have known better than to let a tremble into my voice, should have known that if someone wanted me dead it’d be here, the only place I came to regularly.

Meiko Ko's works have been published by Hayden's Ferry Review, The Literary Review, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Crab Orchard Review, failbetter, Juked, The Hong Kong Review, The Offing, Longleaf Review, Cha: An Asian Literary Journal, Atticus Review, among other places, and forthcoming in the Sleepingfish magazine and Inscape. She was a Pushcart and Best Small Fictions nominee, finalist for the 2020 Puerto del Sol contest, and was longlisted for the 2017 Berlin Writing Prize. Her writing has received support from Bennington Writing Seminars, VONA, Kenyon Review, and One Story.